International attention has been drawn to the issue of gender differences this week by a Canadian couple who are trying to raise their child, Storm, as “genderless.” While the couple is taking a rather extreme approach by not revealing the sex of their baby to anyone, progressive parents around the world have been attempting gender neutrality on a smaller scale for years, changing the protagonists in children’s stories to gender-neutral pronouns, dressing their child in androgynous clothing, and giving them gender-free toys to play with. These well-intentioned parenting practices raise the age-old question of nature vs. nurture, asking whether gender roles are socially formed or biologically entrenched. Of course, the answer is both. While many facets of gender identity are created through social suggestions and pressures, it is difficult to accept that all differences between the sexes are determined by the vocal intonation used when children are infants and the directed encouragement they receive in school as adolescents.

From a more empirical standpoint, there have been a number of articles and books published in recent years arguing the extent to which gender forms our identities, and asking whether these identifiers are more socially or biologically driven. From the nature perspective, Louann Brizendine’s book The Female Brain argues that men and women are inherently and neurologically different. She asserts that a greater proportion of neuronal space in females is allocated to communication, empathy, and nurturing, largely driven by the presence of female hormones such as estrogen and progesterone, coupled with a comparative decrease in androgens in the womb. On the other hand, men, according to her, have a natural affinity towards building and map-reading, stemming from their greater visuospatial skills, as well as higher levels of aggression driven by increased testosterone. It should be noted that Brizendine’s book has been widely criticized for being too broad-sweeping, as well as receiving the much more serious accusation of being largely unfounded and based upon erroneous or unsupporting academic papers from which she takes her references.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, Cordelia Fine’s book Delusions of Gender argues that nearly all differences seen today between men and women are a result of social factors and are largely fabricated by our cultural cloth. She blames early expectations placed upon the child and subtle (or not so subtle) pushes towards social studies and language arts for girls (not to mention pink ponies and Barbies), and math, science, and monster trucks for boys for the gender gaps seen in today’s technical and professional fields. She takes issue with Cambridge psychologist Simon Baron-Cohen’s research on the “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” task I described in my previous post, suggesting expectation effects are to blame for the gender performance differences seen (females typically score higher than males). She also insinuates that researcher bias is at the root of another similarly designed task used in infants, in which female babies are reported to spend more time looking at faces while male babies gaze longer at toy mobiles.

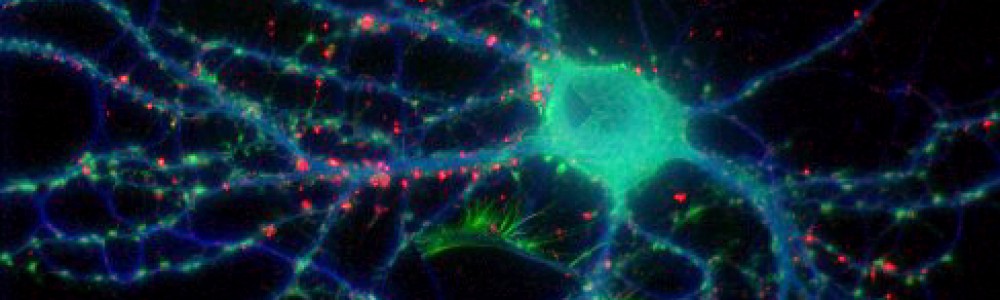

It is incredibly difficult to parse apart the differences seen in our genders. Without a doubt, certain aspects of gender are socially entrenched, like shaming boys for being effeminate or choosing a nurturing career such as nursing, or discouraging girls from trying their hands at the male-dominated fields of engineering or computer science. However, it is ignorant to deny that there are hormonal and anatomical differences between the sexes that in some way influence and make up who we are as individuals. Differences in the size and proportion of neuroanatomical structures have been reported many times in the brains of males and females, and there is no doubt that the different balance of chemicals coursing through our brains and bodies has an effect on us.

An interesting and potentially revealing population that might provide great insight into this nature-nurture gender debate is that of transgender individuals, both pre- and post-transformation. In a fascinating article published this month in the New York Times, Chaz (formerly Chastity) Bono, the transgender son of Cher and Sonny Bono, reported differences in his attention, emotions, and interests after beginning hormone treatment in the course of his transition. Chaz reported feeling an almost immediately greater affinity for gadgets after starting his treatment and much less of an inclination towards talking or gossiping. However, he said that he did not notice these differences when he first began living as a man; it was not until he began taking testosterone that he noticed this adjustment. In the article, he states, “I’ve learned that the differences between men and women are so biological. I think if people realized that, it would be easier. I would be a great relationship counselor. I know the difference that hormones really make.”

Certainly these issues are not so clear-cut, and there are an infinite number of factors that influence where an individual lies on the spectrum of gender identity. An interesting and novel approach to this issue would be to study the truly unique and untapped perspectives of transgender individuals, for which there is currently a dearth in the literature. As for the baby in Canada? It will remain to be seen whether the experiment with Storm will result in a well-adjusted and unbiased individual full of opportunities, or just another confused adolescent struggling to find his or her place in society.