It seems like we are always looking for a quick and easy weight loss solution. We spend millions of dollars every year on gym memberships, workout equipment, dietary supplements and self-help books in the vain attempt to lose those last 5 (or 10 or 20) pounds. Unfortunately, most of these attempts fail miserably and we end up right back where we started, if not worse. But what if there was an easier way? What if there was one simple solution to losing all that excess weight for good? What if all it took was a stool transplant. Would you do it?

Yes, fecal matter. That embarrassing brown lumpy bodily expulsion. We learned from an early age that Everyone Poops, and now a recent study has hinted that with the right transfer, somebody else’s poop could help you lose weight.

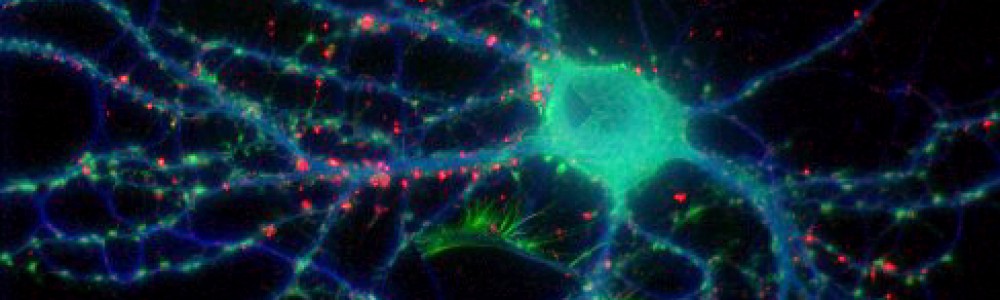

But let’s not get too far ahead of ourselves and take a look at the real science first. The concept of a personal microbiome, a unique bacterial make-up as individual as our DNA, has been gaining traction over the last few years. Gut bacteria, or ‘microbiota’, have been implicated in everything from food allergies to obesity, with some studies suggesting that these bacteria may account for up to 20% of our differences in body weight. Stool samples are teeming with these microbiota, and previous studies have used fecal transfers to replenish lost essential bacteria that help fight infections after they’ve been wiped out with antibiotics.

Research from scientists at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles has recently confirmed that some strains of bacteria can contribute to weight gain, helping people to retain and store calories more easily by aiding in the digestion of nutrients. These bacteria appear to make the stomach and intestines more productive, breaking down food faster and more efficiently so that more nutrients and calories can be absorbed. While this may have been beneficial to our hunter-gatherer ancestors, when food was scarce and mostly consisted of difficult-to-digest plants and animals, today it may be contributing to our problems with over-nourishment and obesity. In the current study, people with greater levels of these bacteria, determined either through stool samples or breath tests measuring hydrogen and methane – by-products of this nutrient break-down – had higher BMIs and body fat percentages than those with lower trace products of the bacteria.

But if your breath tastes especially methaney, don’t despair. According to recent research, there are now several ways to change your gut microbiota.

Physicians have long used gastric bypass surgery to aid in weight loss in cases of extreme obesity. The procedure involves removing up to 80% of an individual’s stomach and can result in weight loss of 75% of excess body weight. This dramatic success was initially thought to be driven by the reduction in stomach size, resulting in a lower capacity for consumption and absorption calories. Simply put, the smaller your stomach, the less food you can eat. However, new evidence suggests that a shift in gut bacteria may also aid in this change.

The microbiota of obese people is markedly different from those of lean individuals, contributing to and perpetuating weight problems. This bacterial profile is partly influenced by what we eat, and it turns out that changing the size of the stomach and intestines can also dramatically alter the make-up of these bacteria. A study published in Science Translational Medicine by researchers from Massachusetts General Hospital recently demonstrated this effect in mice, hinting that it also might apply to people.

In the study, animals who had undergone gastric bypass operations showed not only significant weight loss, but also a dramatic change in microbiota, potentially both resulting from and furthering their weight-loss. Notably, this change was larger and more stable in mice who had had the surgery than in those who lost a similar amount of weight through diet changes, but without the operation. The bypass mice also had greater fecal fat content (yes, we’re back to poop again), suggesting that the new gut bacteria make-up was limiting the break-down and digestion of fat, meaning more was passed through the body without being absorbed.

Previous research has suggested that body weight and fat can also be influenced by transferring lean animals’ intestinal bacteria into obese mice, and vice versa. To test this effect in the current study, gut bacteria from the bypass mice were inserted into new animals through intestinal content transfers – i.e. fecal matter transplants. Sure enough, these ‘donations’ from the bypass mice resulted in significant reductions in body weight and fat levels in the receiving animals, but interestingly did not affect food intake.

As fascinating as these results are, some important questions remain. Firstly, is this a long-lasting effect? Could stool bacterial transfers from lean individuals be a long-term solution to obesity, or would these effects fade away as the transferred super-bacteria die off and are replaced by the host’s natural ones? To date, no studies have followed up these effects long-term, so this remains to be seen. Also, like much innovative scientific research, these results come with ethical questions to consider. Does having a different type of gut bacteria change our responsibility for our own weight and healthy diet? And should we all receive an injection of lean bacteria to prevent future obesity and related health problems?

So what do you think, would you do it?