Imagine you have a piece of chocolate. Unwrap it, place it on your tongue. Savor its decadence as it melts in your mouth; relish the bitter and sweet coating your taste buds; indulge in its creamy texture. As the chocolate dissolves, signals are sent throughout your body. Chemicals are released, reinforcing its rewarding properties and preparing your body for the rush of sugar it is about to receive. You swallow. Immediately you want another piece.

The pleasure of eating is one of our most natural joys, be it savoring a perfectly cooked steak or delighting in that melt-in-your-mouth chocolate. But with the rise of obesity and related maladies – particularly cardiovascular disease, hypertension and type-II diabetes – such simple pleasures have been perverted, pathologized by experts and classed as a source of harm. With nearly 25% of English adults qualifying as obese, and with ensuing costs to the NHS reaching £5.1 billion each year, the UK is facing a self-induced public health pandemic. But how has this happened? And why can’t we all just put down that second piece of chocolate?

Added sugars have become the focus of widespread concern among doctors and researchers, their effects on our waistlines, livers, and even our brains, giving cause for alarm. Obesity specialist Dr. Robert Lustig has emerged as a crusader for the anti-sugar movement, contending that sugar, not fat, is behind the dramatic rise in ‘western diet’ conditions over the past 30 years. The problem stems from the way our bodies metabolize fructose – half of the refined sugar molecule, sucrose – as opposed to pure glucose, which makes up the other half and is found in foods like potatoes and white bread.

Glucose is metabolized by all cells in the body, whereas fructose is primarily processed by the liver. If the liver cannot adequately break down sugar into energy it is converted into fat, and the faster the body receives fructose, the more likely this is to happen. High fructose sugar solutions, like fizzy soft drinks, are particularly prone to this fat conversion, providing high volumes of fructose that reach the liver much more quickly. This inability to break down sugar and the subsequent rise in liver fat is believed to be at the root of insulin resistance, the main deficiency underlying type-II diabetes.

But regardless of doctors’ warnings and the evidence that increased sugar consumption leads to obesity, as well as liver and heart disease, our sugar intake continues to rise. This may be due to the seemingly addictive qualities of high-sugar foods themselves. For despite our best intentions to cut out the cake, doing so rivals quitting smoking in terms of difficulty. New research indicates that foods high in fat or sugar may qualify as addictive substances, causing similar neurochemical changes in the brain as drugs of abuse.

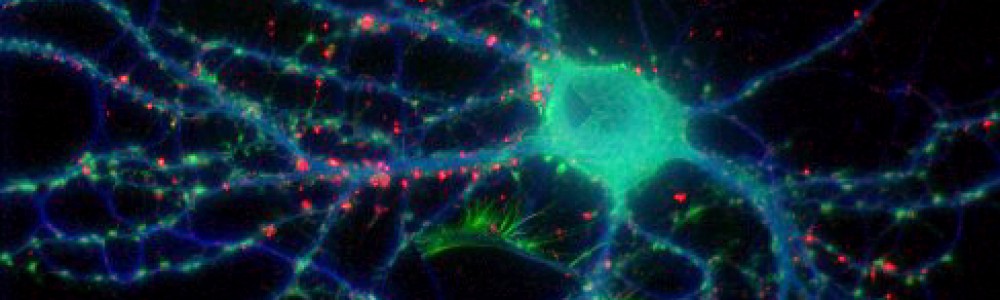

Researchers at Princeton University have demonstrated this phenomenon by intermittently exposing rats to a sucrose solution in addition to their regular food. After a month, rats began to show binge, craving and withdrawal-like behaviors for sucrose, self-administering extremely large quantities when it was available. Adaptations similar to those seen in cocaine-addicted animals emerged in the rats’ brains, with surges of dopamine released during a binge – a process linked to feelings of reward and novelty, and a key facet of drug addiction. An increase in craving was also seen in the test animals, demonstrated by greater sucrose-seeking when deprived of the solution, even in the face of punishment. Additionally, rats experienced withdrawal-like symptoms when the sugar was removed, exhibiting tremors, head-shakes and signs of anxiety and aggression. Such behavior is typically seen in animals going through opiate withdrawal, and is caused by the release of endogenous opioids in the brain by high-sugar foods, reinforcing their hedonic characteristics and creating a withdrawal effect when removed.

Given sugar’s apparently addictive properties, one proposed response to the obesity epidemic is to regulate its availability in much the same way as tobacco and alcohol. Labeling foods high in sugar and fat as ‘addictive’ could potentially remove the stigma attached to being overweight, re-characterising it as a complex medical condition rather than simply one of personal weakness and poor self-control. Furthermore, tougher regulations on the advertising and availability of junk food might help to reduce the proliferation of cheap high-fat/high-sugar snacks that has made diet control increasingly difficult. However, taking responsibility for diet out of the hands of individuals also diminishes personal accountability and the imperative for each of us to make positive food choices. The fast food industry certainly isn’t helping us to lose weight, but it’s also not forcing the food down our throats. Should we be trusted to control what we put into our bodies, or do we need someone to stop us from taking that second piece of chocolate?

*So this post is a bit cheeky. I originally wrote this as a submission for a writing competition, but seeing as how it was never published, I figured it made an apt piece in honor of New Year’s resolutions!

(Thanks to Paul Sagar for help in editing the original piece.)