My favorite holiday is on Thursday. And while I can’t be at home in the States to celebrate, being an ex-pat at Thanksgiving does have its perks, as I get to attend multiple alternate feasts over the weekend. That means twice the stuffing, twice the cranberries, twice the turkey, twice the tryptophan.

Yes, tryptophan. That infamous amino acid we use to justify dozing off during our aunt’s vacation slideshow after the big meal. Tryptophan is an essential amino acid, a protein precursor that the body uses to build various chemical structures. This includes serotonin, one of the primary neurotransmitters in the brain that is involved in everything from decision-making to depression. Serotonin is also a precursor to melatonin, which is important in sleep and wakefulness and is where the tryptophan-tiredness link comes in. However, despite the popular neuro-myth, turkey is actually no higher in tryptophan concentration than other types of poultry. Numerous different plant and animal proteins provide us with our daily doses of tryptophan, with sunflower seeds, egg whites and soy beans having some of the highest concentrations of the amino acid. In fact, turkey comes in at a measly 10th on the list of tryptophan sources.

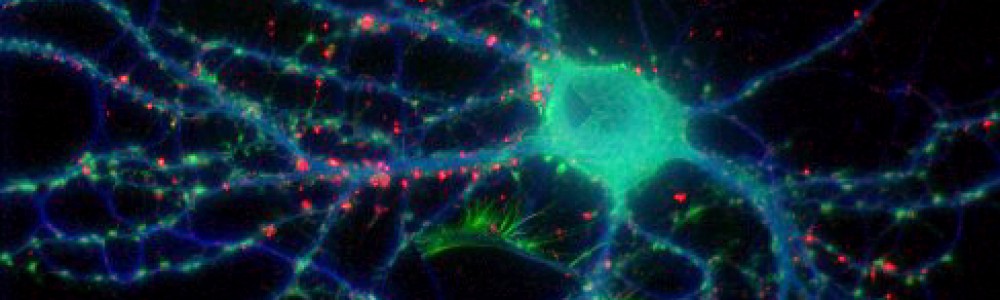

Instead, the relation between eating and sleeping seems to be more dependent on the amount of food consumed, rather than the type we eat. Insulin is released after every meal, particularly ones high in carbohydrates, and the more carbs consumed, the more insulin is produced. This increase then changes the chemical levels in our bloodstream, affecting the re-uptake and release of various amino acids. Ultimately these changes result in greater amounts of tryptophan crossing the blood-brain-barrier and being taken up into the brain. There the tryptophan is converted to serotonin, some of which is also metabolized into melatonin, causing our postprandial nap.

Tryptophan’s influence on serotonin levels doesn’t just affect sleep cycles. The link between depression and low serotonin levels is well established, and tryptophan supplements have been suggested as less invasive treatments for the disorder. Unfortunately these studies have been mostly unsuccessful to date, as mild modifications of tryptophan seem to have little to no effect on mood in most individuals. However, it is possible that people with low endogenous levels of tryptophan due to specific genetic profiles may be more susceptible to the chemical’s effect on mood, and current research is still ongoing in the matter.

So regardless of whether it’s turkey, stuffing or sweet potatoes you prefer, remember to load up your plate during Thanksgiving to get those happy drowsy effects later. It may just help you feel a little bit calmer, and prevent some of the Black Friday mayhem the next day.